How Intrinsic Motivation Can Help You Raise Self-Motivated Kids

/Note: This post contains affiliate links. Parent Remix is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. This means that I may receive a small commission (at no cost to you) if you subscribe or purchase something through those links.

We are all well-meaning parents, and we want to raise our kids to be the best they can be. As a result, sometimes we resort to bribing them. At school and at the gym and field, I hear variations of these statements all the time:

“If you hit a home run, we’ll buy you Halo 5”

“We’ll give you $50 for every “A” you get in school”

“If we have a good parent-teacher conference with your teacher, we’ll plan that party for you”

Heck, I’m guilty of bribing my kids too. And sometimes it works! But something inside me knows there’s a problem with this approach. Is this a short term bandaid without any long term benefit? Is there a better way to motivate our kids to push themselves to reach their potential in school, in their extracurricular activities, and in life?

Enter intrinsic motivation.

What is intrinsic motivation?

A good definition of intrinsic motivation is “an energizing of behavior that comes from within an individual, out of will and interest for the activity at hand. No external rewards are required to incite the intrinsically motivated person into action. The reward is the behavior itself.” (1)

Said another way, intrinsic motivation is something that comes from inside a person. No bribes needed here.

What is the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation?

Business Dictionary defines extrinsic motivation as, “drive to action that springs from outside influences instead of from one's own feelings.” (2)

Extrinsic rewards are the bribes we talked about earlier. If someone is extrinsically motivated, their willingness to put forth effort into an activity is guided by something outside of the person, for example, a monetary reward or gift. This is the opposite of intrinsic motivation, where the reward is in the enjoyment of the process or behavior.

How Extrinsic Rewards Affect Our Drive to Perform

The research outlined in Daniel Pink’s book “Drive” is fascinating. It flies in the face of everything we believe to be true. At work, we think bigger sales commissions are motivating. At home, we think incentivizing our kids with virtual bucks for their favorite video game makes sense.

However, one of the foremost researchers in the area of motivation, Dr. Edward Deci, found that “reward effects reported in 128 experiments lead to the conclusion that tangible rewards tend to have a substantially negative effect on intrinsic motivation.” (3)

Pink outlines how our beliefs regarding the factors that motivate people were developed back when the work we did was concrete and followed a specific and strict set of rules. There wasn’t room for any creativity, and the tasks were usually boring and uninteresting. (Think factory line workers e.g. “Laverne and Shirley”).

To incentivize workers to maximize production of these routine and boring tasks, companies began rewarding employees for their production. Quotas were set, and monetary rewards were given for meeting or exceeding the quotas. This “industrial-era” view of how we go about our work persists today, although we live in a much different world.

For these types of tasks, monetary (or extrinsic) rewards work well. Daniel Pink says, “For routine tasks, which aren’t very interesting and don’t demand much creative thinking, rewards can provide a small motivational booster shot without the harmful side effects.” (4).

The research seems to confirm this conclusion. Psychologist Dan Ariely conducted a study of motivation in India. Participants were offered three levels of rewards in exchange for completing tasks at varying levels. These tasks weren’t routine; they involved higher order thinking and creativity. The incentives ranged from one day’s pay, two weeks pay, and five months pay. Guess what they found? The group offered the largest reward did worse in 8 of the 9 tasks the researchers measured. Their conclusion: higher incentives led to worse performance for non-routine problems requiring creative solutions.

In his book “Payoff”, Ariely outlines a study he did regarding the effectiveness of large bonuses. He said, “One of our main findings was that when the bonus size became very large, performance decreased dramatically.” (5). He went on to say, “adding money to the equation can backfire and make people less driven.” (6) The results of his studies show that we are driven by more than monetary compensation for the work we do.

Why does this happen? Read on.

How Extrinsic Rewards Affect Creativity and Altruism

In his book “Drive”, Daniel Pink outlines a study where participants were tasked with solving a problem where they needed to find a way to affix a candle to the wall. To accomplish this, they were given a candle, tray, a book of matches, and tacks, and were timed to see how long it took them. The researchers split the groups into two; one group that wasn’t incentivized, and the other incentivized based on how fast they could solve the problem. They found that offering the external reward caused myopia and hampered creativity because “rewards, by their very nature, narrow our focus” and causes us to see only what’s in front of us rather than what’s off in the distance. (7)

In yet another experiment, researchers studied female blood donors in Sweden. They divided women who were interested in giving blood into three groups; in the first group the donation was voluntary, the second group would receive about $7 in compensation for their donation, and the third group would receive about $5 with an option to donate it to a children’s cancer center. The researchers found that paying people decreased the number of potential donors who decided to give blood, and surmised that “it tainted an altruistic act and “crowded out” the intrinsic desire to do something good.” (8)

In addition, Pink states that giving external rewards is addictive and creates a precedent. First, attaching a reward to a task automatically casts it as undesirable. If you offer too small of a reward, people won’t do it, and if you offer something that entices them to actually do the task, you’ll have to offer the reward over and over again.

Stated another way: “A contingent reward makes an agent expect it whenever a similar task is faced, which in turn compel the principal to use rewards over and over again. And before long, the existing reward may no longer suffice. It will quickly feel less like a bonus and more like the status quo—which then forces the principal to offer larger rewards to achieve the same effect.” (9)

To summarize, external rewards can hamper performance and the drive to achieve better results, dull creativity, curb our intrinsic desire to “do good”, narrow our horizons from broad thinking to just what’s in front of us, and can be addictive.

Main Idea: Although it seems counterintuitive, extrinsic rewards can have the opposite of it’s intended effect.

How Intrinsic Motivation Can Help Our Kids at School and in Life

As we discussed earlier, our familiar reward and incentive system was developed when the work we did was routine, dull, and involved following a strict set of rules to completion.

Fast forward to life today. The factory type routine work that our grandparents did is now increasingly automated. For example, Costco has a pizza making “mechanical saucing machine” that applies the sauce so that it spreads the tomato sauce base all over the pizza crust, enabling Costco to prepare a massive amount of pizzas per day. McDonalds and Wendy’s have self-serve kiosks. (10)

As you might imagine, routine tasks will be increasingly automated in the future. And since robots will be doing the routine stuff, the work our kids will be called upon to do will be novel, complex, and will require higher order thinking and creativity.

Research done by Harvard Business School’s Teresa Amabile found that “intrinsic motivation is conducive to creativity; controlling extrinsic motivation is detrimental to creativity.” (11) And researchers are finding that people are not motivated solely “or even mainly by external incentives” (12)

When I was growing up, we learned from textbooks and by rote memorization. Today, experts agree that our kids need to develop “soft” skills and character traits (such as creative thinking and curiosity) in addition to cognitive skills such as problem-solving, critical analysis, the attainment of core subject knowledge, and strong early literacy and numeracy”. They’ll need to learn how to learn, be resilient and work “collaboratively, independently and creatively.” (13)

P21, the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, is an organization comprised of teachers, education experts, and business leaders. Together, they developed the “21st-century student outcomes”; the “skills, knowledge and expertise students should master to succeed in work and life in the 21st century”. (14)

In summary, here are the “21st Century Student Outcomes”:

1. Content Knowledge includes the core subjects including language arts, world languages, arts, math, economics, science, geography, history, and government.

2. Learning and Innovation Skills: Creativity and Innovation, Critical Thinking and Problem Solving, Communication, Collaboration*

3. Information, Media, and Technology Skills: citizens and workers must be able to create, evaluate, and effectively utilize information, media, and technology.

4. Life and Career Skills: Today's students need to develop thinking skills, content knowledge, and social and emotional competencies to navigate complex life and work environments.

*emphasis added by me

Main Idea: Two of the most important skills our kids need to succeed in their lifetimes will be their ability to learn how to learn and think creatively, both of which can be developed and nurtured through intrinsic motivation. Unlike external motivators, which tend to snuff out creativity and narrow our focus, intrinsic motivation allows us to think big-picture and to find creative solutions.

The Three Components of Intrinsic Motivation

Autonomy

There are three factors required for intrinsic motivation. The most critical component of intrinsic motivation is autonomy. (15) According to motivation researchers Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, “Autonomous motivation involves behaving with a full sense of volition and choice, whereas controlled motivation involves behaving with the experience of pressure and demand toward specific outcomes that comes from forces perceived to be external to the self.” (16)

Practically speaking, what does autonomy mean? It means you are acting with choice. To help, use the test of the 3 T’s: Task, Time, and Technique. (17) We can ask ourselves whether or not our kids have choices over what type of tasks to do, when to do it, and how to do it.

The reason autonomy is so important to motivation is that whereas “control leads to compliance, autonomy leads to engagement.” (18)

Mastery

The second element of intrinsic motivation is mastery. Mastery is defined (per dictionary.com) as “comprehensive knowledge or skill in a subject or accomplishment.” In the book “Drive”, mastery is also defined as “the desire to get better at something that matters”. (19)

Mastery involves persevering through setbacks and failures to achieve long term goals. Malcolm Gladwell’s research says it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill. Psychologist Anders Ericcson studied expert performance and established the “deliberate practice” rule; that one must intensely practice over a long period of time to become a master. “Mastery—of sports, music, business—requires effort (difficult, painful, excruciating, all-consuming effort) over a long time (not a week or a month, but a decade)”. (20) Moreover, “A key tenet of deliberate practice is that it's generally not enjoyable.” (21)

So, in order to truly master something, you must press on and do the hard stuff; the stuff no one else wants to do when you don’t feel like doing it. Mastery is a test of true tenacity—it doesn’t happen overnight.

Mastery goes hand in hand with the growth mindset; you must believe you have the ability to learn and grow toward mastering the task. If you have a fixed mindset, wherein you believe that you’re born with a certain level of smarts or ability, you won’t spend the time and effort that is required. Why bother? You weren’t born with that skill set anyway.

With respect to our kids, re-frame mastery as “competence”. In her book, “Self Motivated Kids”, Damara Simmons states, “all children long for the feeling of competence. This means the ability to successfully accomplish a task. Feeling competent in their abilities is a psychological and emotional need felt at their very core.” (22)

Purpose

Finally, the last element of intrinsic motivation is purpose. It’s the “why” behind the actions. Does what you do have deep meaning and significance? Does it contribute to a greater good? Do you understand why you’re being asked to do something?

When people don’t know why they’re being asked to do something, or if they don’t understand how they fit into the big picture, motivation declines.

Main Idea: the three components of intrinsic motivation are autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

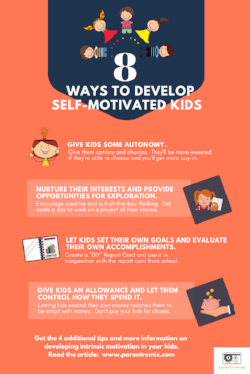

8 Ways To Help Develop Intrinsic Motivation In Our Kids

Let’s be real. Believing that we can instill intrinsic motivation in all areas of life with our kids is unrealistic. If they’re simply not interested in band or soccer, no amount of autonomy, mastery, and purpose is going to change that. (It might make it less painful, though.)

But let’s say there is something that your child is interested in. How can we use the research to nurture intrinsic motivation in our kids so that they flourish in that area? Read on and pick a strategy that feels right and try it on for size.

1. Give Kids Options and Choices

Ask yourself if you’re allowing your child to be self-directed and if he has choices over how to perform tasks, how to utilize his time and the technique he uses to complete his tasks (the 3 T’s discussed above). Are you coming up with the ideas for his group project and then micromanaging their progress? Do you hover over his work and frequently force him to make changes to his assignments? Are you selecting the courses he’s taking?

Instead, step back and see if there’s room to give your child some autonomy over his choices. For a tween or teenager, ask him to set his own goals and outline his roadmap as to how he’s going to get there. I’ll never forget an interview I heard on NPR with Howard Schultz, the founder of Starbucks. Although I can’t recall the exact specifics, I remember him saying that his mother would always ask him “what is your plan?” (for his upcoming tests, projects, etc). She didn’t dictate the time he needed to spend studying, or how he studied. Instead, she forced him to think about his goals and formulate his own plan.

As you might imagine, it’s much easier get buy-in when your child has options and is an integral part of the planning process.

2. Nurture Their Interests and Provide Opportunities for Exploration

Once they’ve made their choices, help to support and nurture their interests and creativity. In the TV show “Project Runway”, the participants are given a theme, and then they’re set free to design their garment, choose their materials, construct the garment and model it in a way that reflects their style.

Allow your kids to flex their creative muscle by setting aside a “Project Runway” type day for them to work on a project of their choosing. Help them to brainstorm and gather materials prior, so they can dive right in on their scheduled day. Let them showcase their completed project the next day and discuss with them the lessons they learned along the way.

Several large corporations, including 3M and Google, allow their employees these creative work days, and it has resulted in some of their best ideas!

3. Have Kids Set Their Own Goals And Evaluate Their Accomplishments

We tend to focus on grades and report cards. For good reason—there’s typically only one scheduled parent-teacher conference per school year, so the report card is all we’ve got. But grades are what Daniel Pink calls “performance goals”. A performance goal focuses solely on the end result (grades). Instead, incorporate “learning goals” into your evaluation of your child’s progress. A learning goal focuses on the process of learning and improving as opposed to the results or outcome.

A learning goal sounds like this: “I’ll be reading novels from the Young Adult Newberry Award Book List” this summer. Or, “I'll learn to speak some basic Japanese phrases by the time we go to Japan this Spring Break.” At the beginning of the school year, work with your child to identify their top few learning goals for the year in the subjects that really interest them.

Then, have your child create their own “DIY report card”. (23) At the end of each semester, have them write a few paragraphs reviewing their progress toward their learning goals. They should evaluate what they did well, and identify where they need some additional work to move toward their goals.

Once they’ve completed their review, compare their report card with the school’s report card. Let the school’s report card be the starting point for a conversation with your child, along with their DIY Report Card.

4. Give Them Their Own Money—But Don’t Use Extrinsic Rewards for Chores

Daniel Pink states that giving children an allowance teaches them how to manage their own money and gives our kids autonomy over how they spend their money. The caveat: don’t tie the allowance to doing chores. Help them to understand the “why” (i.e. purpose) underlying the chores; that chores are done for the benefit of the family and that family members need to help each other out.

If you pay kids for doing chores, it teaches them the only reason to do the task (clean the bathroom, washing the dishes, taking out the trash) is to get paid to do it. (24)

5. Praise Effort and Process, Not Intelligence and Results

Based on Carol Dweck’s research on the growth mindset, Pink concurs that parents should praise a child’s effort, not their intelligence. With a focus on the effort involved in the process of learning, “students don’t have to feel that they’re already good at something in order to hang in and keep trying. After all, their goal is to learn, not to prove they’re smart.” (25)

Focus on the process; the love of learning and improving versus strictly the results (grades or athletic achievements). Also, focus on being specific and providing useful information to our kids about what they’ve done. Don’t give fake praise. Be genuine.

6. Celebrate Their Accomplishments

In his book “Payoff”, Dan Ariely states that as human beings, we are all driven by “intangible, emotional forces: the need to be recognized and to feel ownership, to feel a sense of accomplishment, to find the security of a long-term commitment and a sense of shared purpose.” (26)

Celebrate your kids’ accomplishments as they work toward their learning goals. This type of positive reinforcement from a parent is priceless and goes a long way in motivating your child.

7. Help Kids Develop Mastery (Competence)

One of the best ways to foster competence in a child is to help him learn and master new skills. Damara Simmons states one of the best ways to do this is to use a strategy called “elbow parenting”, where your child is learning and doing the task along with you. (27) For younger children, do a task together, like preparing a sandwich or washing the car.

For older children, model the behavior that helps to develop expertise. For example, talk to your kid about accepting the invitation to present a lesson in front of your entire department at work. This shows them how you are working on mastering presentation skills by stepping outside your comfort zone. Talk to him about putting in your application for a big promotion where you’re up against some pretty tough competition, thereby showing off your growth mindset.

8. Help Kids Discover Their Purpose

Let’s help our kids with big-picture thinking. Help them to understand: Why are they learning something? How does it pertain to the world they live in? Why is what they’re doing important?

One of the best ways to do this is to have them use their skills in real life. By showing them how it relates to the real world, they may see the bigger picture. If they’re learning Chinese, take them to Chinatown so they can practice speaking their new language. The benefits are twofold: it’ll help to foster a global perspective and help them learn their new language! Also, give kids an opportunity to teach something they’re enthusiastic about. Teaching is one of the best ways to help them truly master what they’re learning. Ask your child to teach you some basic coding, or have him tutor a struggling classmate.

Help your child change his mindset about the tasks before him. Ask him to think about how his actions contribute to a larger good. For example, if the subject is science, explain how he can connect learning science to optimizing his nutrition and conditioning for the sports he’s involved in. Then, show him how he can use the lessons learned to achieve a higher purpose: to help his friends and family eat right, exercise and lead healthier and longer lives.

So, there you have it. I hope this post gave you some food for thought about how using external rewards can fail to provide the motivation you’re hoping to develop in your child (and what to do instead). If you found this post helpful, please share it with friends on Facebook or pin it to your Pinterest boards. And don’t forget to sign up below to get more parenting resources (in our awesome resource library) and to be notified when new articles are published!

Until the next time….

REFERENCES:

(1) Michigan State University; https://msu.edu/~dwong/StudentWorkArchive/...RIP/Webber-IntrinsicMotivation.htm

(2) http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/extrinsic-motivation.html

(3) Pink, Daniel H. "Drive The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Riverhead Books. 2009. p. 37. Also: (4) 60, (7) 42, 55, (8) 47, (9) 53, (11) 29, (12) 27, (15) 88, (16) 88, (17) 92, (18) 108, (19) 109, (20) 122, (23) 188, (24) 188, (25) 120.

(5) Ariely, Dan. “Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations”. Simon & Schuster, 2016. p. 58. Also: (6) 67, (26) 101.

(10). Hanbury, Mary. “Costco’s mesmerizing, pizza-making robot is an ominous sign for American retail jobs”. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/costco-pizza-sauce-robot-2018-4. Accessed 30 April 2018.

(13) Siraj, Iram. “Teaching kids 21st-century skills early will help prepare them for their future”. The Conversation. www.theconversation.com/teaching-kids-21st-century-skills-early-will-help-prepare-them-for-their-future-87179. Accessed 27 April 2018.

(14). P21 Partnership for 21st Century Learning. http://www.p21.org/our-work/p21-framework. Accessed 27 April 2018.

(21). Lebowitz, Shana. “A top psychologist says there's only one way to become the best in your field — but not everyone agrees”. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/anders-ericsson-how-to-become-an-expert-at-anything-2016-6. Accessed 30 April 2018.

(22). Simmons, Damara. “Self Motivated Kids”. p. 523. Also: (27) 558.